Dead Language

Tereza Zelenková’s work has always drawn deeply on a certain strand of darkly imaginative literature, whether the transgressive musings of Georges Bataille or the lyrical poetry of Rimbaud and Baudelaire. In this series, she has allowed her imagination to roam even more freely, making connections between the visual and the written, while simultaneously acknowledging a frustration with the limits of the purely photographic. In Dead Language, her solo exhibition at Josef Sudek’s Atelier, Zelenková summons up the spirits of diverse writers, artists and thinkers, as well as the lingering ghostly traces of analogue photography in her deftly discursive merging of image and text. The viewer – though reader might be a more apt word here – is thus taken on a tangential journey into the realm of often esoteric interconnected ideas. In The Skull of Descartes, language itself is interrogated and meaning questioned. In The Language of Moths, the migratory journey of the death’s-head hawkmoth is compared to the voyage of Count Dracula, while both are contrasted with the contemporary migrant trails and the fear and suspicion they provoke in Western culture. “The photograph is not the end product or indeed the starting point,” elaborates Zelenkova of her way of working, “Instead, it is about my abiding interest in the actual subject of the photograph or the story behind it. In this instance, I am not making work that explores a single subject deeply. It is more about collecting sometimes rather fragmented information that resonates with each other, pushing the meaning beyond what is commonly expected.”

Text: Sean O’Hagan, writer, The Guardian

Image: Tereza Zelenkova, Moth, 2020

Image: Tereza Zelenkova, The Skull of Descartes, 2020

Image: Tereza Zelenkova, Dead Language, Ateliér Josefa Sudka, 2020

The Skull of Descartes

The skull of the French philosopher René Descartes disappeared, together with the index finger from his right hand, during the transportation of his bodily remains from Sweden to France in 1666, sixteen years after his death. Afterall Descartes is not the only important figure who was posthumously robbed of his bodily parts. The same destiny was met by others, such as Emanuel Swedenborg (the story of his skull would require a separate chapter), Joseph Haydn, Ludwig van Beethoven, or Sir Thomas Browne. Browne himself foresaw the destiny awaiting his remains when he wrote that who is to know the fate of his bones, or how often he is to be buried?

It was only in 1823 when a skull appeared, covered with writings in Swedish and Latin that attributed it to Descartes. The skull was sent to France, where it was examined by Georges Cuvier who would try to prove its authenticity because at that time there were five other skulls assigned to the French philosopher. Cuvier would measure the skull and compare it to the best-known likeness of Descartes – a portrait painted by Dutch painter France Halse in 1649. However, the authenticity of the portrait is disputable, similarly like the authenticity of the skull itself. Although it is possible that Halse’s painting is not faithful, Cuvier wasn’t the last one who would try to authenticate the skull by comparing the two. In 1913, the anatomist Dr. Paul Richer made a plaster cast of the skull in question and consequently placed it within a plaster bust based on Halse’s portrait. His motivation was to prove beyond doubt that the skull’s shape and proportions correspond with the physical attributes of Descartes’s face. The resulting object is a plaster bust statue with removable parts of its face, revealing the skull hidden beneath its surface.

This unusual representation unintentionally epitomizes Descartes’s best-known concept of dualism of body and soul. According to Descartes, the human body is merely a vessel, some kind of machine, and our soul dwells inside the so-called pineal gland, an organ which can be found in the centre of one’s head. This only unpaired part of our brain is supposedly the place where all ideas are formed and therefore it is a constituent element of the Cartesian concept of existence, summarised in the famous phrase cogito ergo sum, or I think therefore I am. Yet, if the only manifestation of our existence is the act of thinking, isn’t it necessary to take into account the prerequisite for our ability to form and process thoughts – the language? Language cannot exist within one enclosed system, for example our mind, because it would not be able to produce any fixed meaning. Descartes wouldn’t be able to form rational thoughts if the words he uses wouldn’t make sense. The existence of language rests on the illusion of tying words to the signified as if they were directly bound. Similarly, isn’t it the case with graves that they’re purpose is, among other, to certify the illusion of an existing bond between one’s name and his or her body? The missing skull that refuses to be buried, and through that named beyond doubt, is like the ever-elusive concept of the human soul that resists to be fully grasped and described by the very language that supposedly certifies its existence.

Text: Tereza Zelenkova

Bibliography:

W. G. Sebald, The Rings of Saturn, 1995

Michael Taussig, Walter Benjamin’s Grave, 2006

The skull of the French philosopher René Descartes disappeared, together with the index finger from his right hand, during the transportation of his bodily remains from Sweden to France in 1666, sixteen years after his death. Afterall Descartes is not the only important figure who was posthumously robbed of his bodily parts. The same destiny was met by others, such as Emanuel Swedenborg (the story of his skull would require a separate chapter), Joseph Haydn, Ludwig van Beethoven, or Sir Thomas Browne. Browne himself foresaw the destiny awaiting his remains when he wrote that who is to know the fate of his bones, or how often he is to be buried?

It was only in 1823 when a skull appeared, covered with writings in Swedish and Latin that attributed it to Descartes. The skull was sent to France, where it was examined by Georges Cuvier who would try to prove its authenticity because at that time there were five other skulls assigned to the French philosopher. Cuvier would measure the skull and compare it to the best-known likeness of Descartes – a portrait painted by Dutch painter France Halse in 1649. However, the authenticity of the portrait is disputable, similarly like the authenticity of the skull itself. Although it is possible that Halse’s painting is not faithful, Cuvier wasn’t the last one who would try to authenticate the skull by comparing the two. In 1913, the anatomist Dr. Paul Richer made a plaster cast of the skull in question and consequently placed it within a plaster bust based on Halse’s portrait. His motivation was to prove beyond doubt that the skull’s shape and proportions correspond with the physical attributes of Descartes’s face. The resulting object is a plaster bust statue with removable parts of its face, revealing the skull hidden beneath its surface.

This unusual representation unintentionally epitomizes Descartes’s best-known concept of dualism of body and soul. According to Descartes, the human body is merely a vessel, some kind of machine, and our soul dwells inside the so-called pineal gland, an organ which can be found in the centre of one’s head. This only unpaired part of our brain is supposedly the place where all ideas are formed and therefore it is a constituent element of the Cartesian concept of existence, summarised in the famous phrase cogito ergo sum, or I think therefore I am. Yet, if the only manifestation of our existence is the act of thinking, isn’t it necessary to take into account the prerequisite for our ability to form and process thoughts – the language? Language cannot exist within one enclosed system, for example our mind, because it would not be able to produce any fixed meaning. Descartes wouldn’t be able to form rational thoughts if the words he uses wouldn’t make sense. The existence of language rests on the illusion of tying words to the signified as if they were directly bound. Similarly, isn’t it the case with graves that they’re purpose is, among other, to certify the illusion of an existing bond between one’s name and his or her body? The missing skull that refuses to be buried, and through that named beyond doubt, is like the ever-elusive concept of the human soul that resists to be fully grasped and described by the very language that supposedly certifies its existence.

Text: Tereza Zelenkova

Bibliography:

W. G. Sebald, The Rings of Saturn, 1995

Michael Taussig, Walter Benjamin’s Grave, 2006

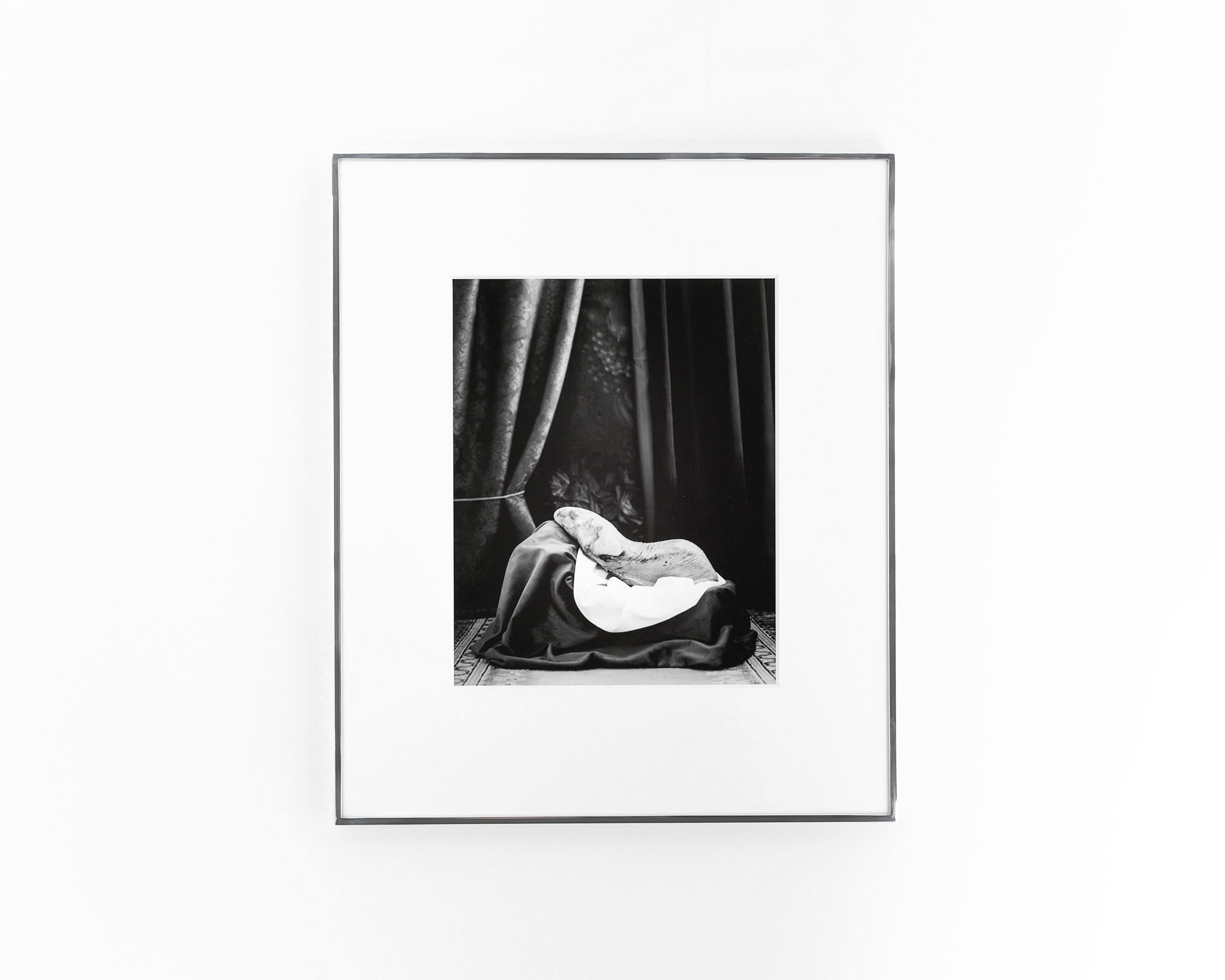

Image: Tereza Zelenkova, The Language of Moths, 2020

The Language of Moths

“For the dead travel fast.”

–Bram Stoker, Dracula, 1897

The death’s-head hawkmoth (Acherontia atropos) gets its name after the shape on the back of its head that’s reminiscent of a skull. Together with the patterns on its body that look like skeletal ribs and its wings forming some kind of cloak, this creature’s appearance can be immediately compared to that of a grim reaper. Indeed, even its name, Acherontia, is derived from the Greek name for the River of Pain in the Underworld, Acheron. Thanks to its appearance, finding one of these moths in the house has been widely perceived as a bad omen. It is seen as a messenger of evil spirits and some believe it is supposed to foretell war, hunger and death. All of this thanks to its unusual appearance and people’s superstitious nature.

Death’s-head hawkmoth is at home throughout tropical Africa and surrounding areas, but it often migrates impressive distances and therefore can be found in many regions of Europe. It is actually considered to be the fastest flying moth specie in the world. “For the dead travel fast”, as Bram Stoker writes in Dracula. Of course, similarly as the death’s-head hawkmoth travels form South to North, Dracula travels from East to West, both reversing the common colonial narratives, and as such, posing a threat to the established order. Both Dracula and the death’s-head hawkmoth perhaps best embody the fears of the migration processes at work in today’s world. Fueled by fear of the Other, often built on superstitions and preconceived judgements, contemporary migrants from parts of Africa and from the East also represent a bad omen to a substantial portion of the Western population. While we continue our exploitation of other cultures and countries, we hold on to the irrational fears that betray our own false narratives of advanced societies built on empirical science and intellectual superiority. We derive our material wealth from other countries while we refuse to share it with their people, living in the perpetual fear of the Unknown that is coming to haunt our moral complacency.

Text: Tereza Zelenkova

Bibliography:

Bram Stoker, Dracula, 1897

Iain Robert Smith, Transnational Film Remakes, 2017

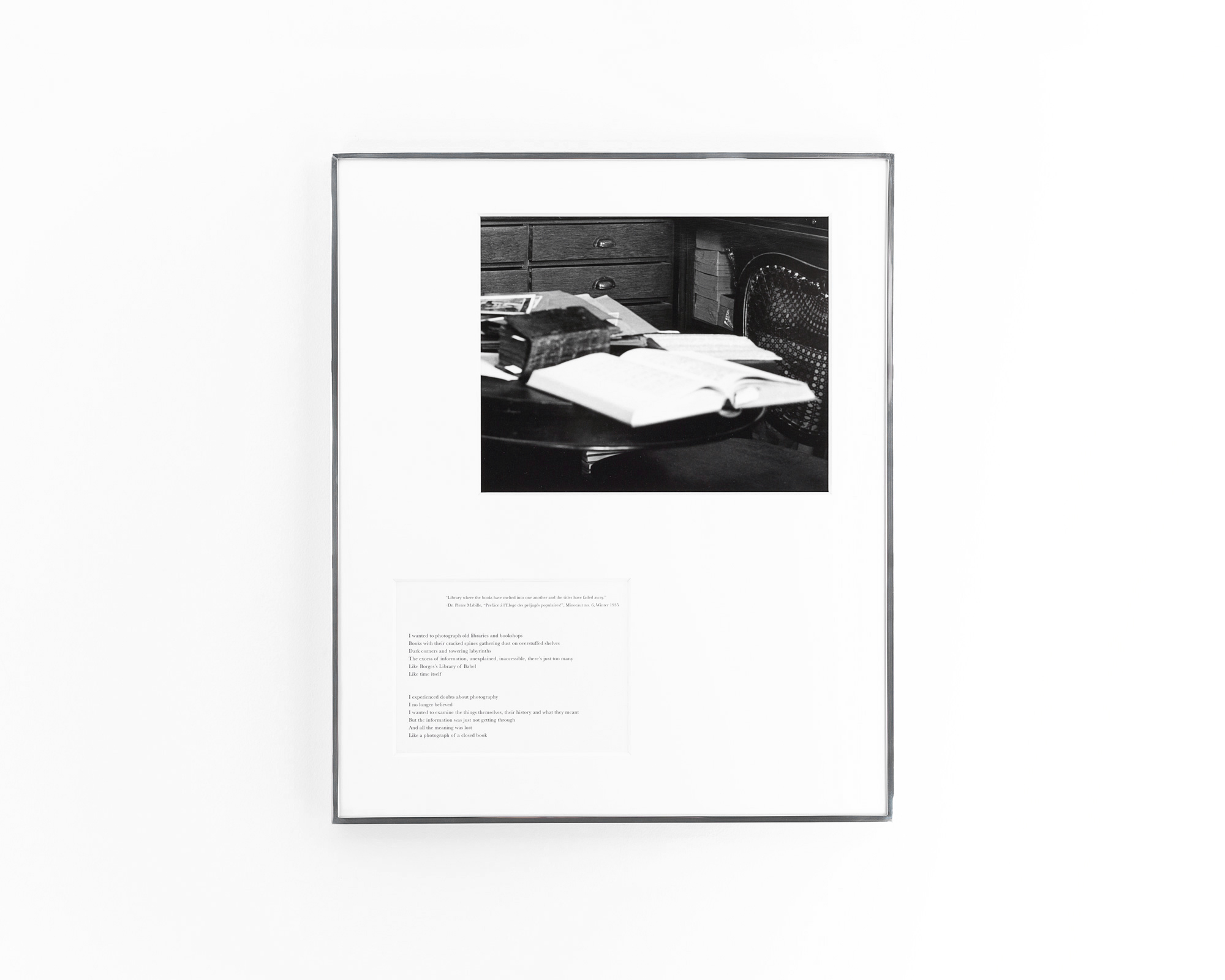

Image: Tereza Zelenkova, The Open Book, 2020

The Open Book

“Library where the books have melted into one another and the titles have faded away.”

–Dr. Pierre Mabille, “Prefáce á l’Eloge des préjugés populaires!”, Minotaur, 2, no. 6 (Winter 1935, p.2)

I wanted to photograph old libraries and bookshops

Books with their cracked spines gathering dust on overstuffed shelves

Dark corners and towering labyrinths

The excess of information, unexplained, inaccessible, there’s just too many

Like Borges’s Library of Babel

Like time itself

I experienced doubts about photography

I no longer believed

I wanted to examine the things themselves, their history and what they meant

But the information was just not getting through

And all the meaning was lost

Like a photograph of a closed book

Text: Tereza Zelenkova

Image: Tereza Zelenkova, The Secret Language of Images, 2020

The Secret Language of Images

Leafing through the book on Courbet, I came across L’Origin du Monde. It brought back memories related to times when I first saw it at Museé d’Orsay, during the weeks spent travelling, strolling through the streets of this and that city, all the while experiencing an overload of new sensations. I would take long walks, visiting places where the writers I was reading used to live. Among them also 5 Rue de Lille, home to Jacques Lacan, the last private owner of the painting.

Just like that, images creep their way into our lives, taking on significance that one would never anticipate. Pictures have their own secret language that translates differently to everyone and like music, we can even endow them with meaning that’s unique to our own lived experience. This brings forth questions surrounding the inherent miscommunication that might arise from any attempt at interpreting them. It is as if we were all mumbling to ourselves within the echo chambers of our consciousness. Yet it seems there’s affinity among a number of people, when the invisible becomes visible and ideas and images suddenly stand clear and their meaning, however obscure, resonate with one another.

Text: Tereza Zelenkova

Image: Tereza Zelenkova, Plaster cast of a dissected hand, 2020

Image: Tereza Zelenkova, Plaster cast of a dissected hand, 2020 Image: Tereza Zelenkova, Dead Language (Mrtvý jazyk), 2020

Image: Tereza Zelenkova, Dead Language (Mrtvý jazyk), 2020 Image: Tereza Zelenkova, The Language of Moths, 2020

Image: Tereza Zelenkova, The Language of Moths, 2020 Image: Tereza Zelenkova, The Secret Language of Images, 2020

Image: Tereza Zelenkova, The Secret Language of Images, 2020

Images: Tereza Zelenkova, Dead Language, exhibition views, Ateliér Josefa Sudka, Prague, 2020

Images: Tereza Zelenkova, Dead Language, exhibition views, Ateliér Josefa Sudka, Prague, 2020Copyright: Tereza Zelenkova, 2022